WASHINGTON -- In the summer of 2002, the pharmaceutical company Organon unveiled what it believed would be a game-changer in the multibillion-dollar birth control industry. Its product, NuvaRing, was the first hormonal contraceptive vaginal ring in the world. An easy-to-use device that relieved women of the burden of taking a pill on a daily basis, it was hailed as the greatest advance in contraception since the introduction of the pill in 1960.

"We've never seen anything like this in my lifetime," Dr. Carolyn Westhoff, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology who worked on NuvaRing's clinical trials, told Newsday that August.

"It's really an exciting time for contraceptive users," Dr. David Grimes, a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina, told The Washington Post. "It's a new era."

Before NuvaRing could be marketed in the United States, however, it needed the approval of the Food and Drug Administration, and the FDA had some concerns. Most hormonal contraceptives carry a risk of blood clots, with a higher risk of cardiovascular events among women who smoke, especially if they are over the age of 35. But in one of the clinical trials for NuvaRing, a healthy woman in her 20s had developed a blood clot -- a surprising occurrence that an investigator determined was probably related to the birth control device.

As a result, the FDA said Organon should include a statement in NuvaRing's packaging insert specifically mentioning the clinical trial and warning women and health care providers that the ring might carry a higher risk of causing blood clots -- formally known as venous thromboembolism, or VTE -- compared with other hormonal contraceptives.

Organon executives adamantly opposed such a statement. They had invested major resources in developing the new device and had secured a patent that promised to bring in billions of dollars in profits if it became a success. They were planning to market it not only as innovative and easy to use but as delivering lower, and thus safer, doses of hormones. An elevated VTE warning label would have been a huge blow. Such a warning might have discouraged women from using NuvaRing and made doctors less inclined to prescribe it -- significantly cutting into the potential return on investment.

"We should really try to get it out of the text," Wim Mens, from Organon's regulatory affairs division at company headquarters in Oss, Netherlands, wrote to colleagues in an email in the fall of 2000.

Americans may assume that the fine print in a drug's packaging represents the collective scientific knowledge about that medication, allowing doctors and patients to make informed health care decisions. In fact, negotiations between pharmaceutical companies and the FDA over warning labels are common during the drug approval process, with drugmakers endeavoring to cherry-pick what's included in order to present their products in the best possible light.

"There's always a tug between the FDA and the manufacturer as to what the label is," Sidney Wolfe, founder and senior adviser of Public Citizen's Health Research Group, a public health advocacy organization, told The Huffington Post.

It's a process that's skewed in favor of the drug companies, critics charge. The FDA relies on the manufacturers to provide clinical trial results and other data the agency uses to evaluate their drugs and devices, and 70 percent of the funds for FDA reviews comes directly from the industry through user fees. As a result, Wolfe said, "these battles are tilted even further against public health and safety."

In the case of NuvaRing, Edwina Muir, Organon's director of regulatory affairs in the United States, suggested in 2000 that they agree to some of the FDA's other recommendations, such as including data from animal testing in the packaging insert, as a "bargaining chip" so that they could exclude "more important issues" such as the VTE warning and bleeding data from the clinical trial, according to internal company emails.

By the end of 2000, negotiations with the FDA appeared to be turning Organon's way. Since clinical trials are designed primarily to test for efficacy, rather than safety, the drugmaker argued that the results of the trial should not be taken as evidence that NuvaRing was unsafe. The FDA backed off its initial recommendation and suggested noting simply that it was "unknown" whether NuvaRing had an increased risk of blood clots.

"The label change looks much better," David Stern, Organon's director of U.S. reproductive marketing, wrote in an email to his colleagues on Dec. 22, 2000, "however, I am still unhappy with the VTE section of the label. Obviously the case that we presented to them has made some impact, in that they have added the statement about [it] being unknown if NuvaRing has this increased risk."

Still, Stern asked his colleagues, "What are the chances that this section can be removed altogether?"

Today, NuvaRing is marketed in more than 50 countries, making it one of the most popular forms of birth control in the world. An estimated 1.5 million women use NuvaRing worldwide, and it has been prescribed more than 44 million times over the past decade in the U.S. alone. It is currently manufactured by the pharmaceutical giant Merck & Co., after Organon was acquired by Schering-Plough in 2007 and Schering-Plough merged with Merck in 2009. Last year, sales of NuvaRing generated $623 million globally, according to Merck's 2012 financial report.

While NuvaRing has proven effective for the majority of its users, a growing number of women have come forward with allegations that the birth control device has caused blood clots and other severe side effects.

Lyndsey Agresta, a 27-year-old resident of Cleveland, had been using NuvaRing for barely a month when she began experiencing migraines. She found the pain so unbearable that in June 2008, she called her mother at 3 o'clock one morning to take her to the emergency room and look after her 5-year-old son, Dominic. She said she "couldn't take it anymore," her mother, Diane Agresta, told HuffPost. That was the night, Diane said, that "everything just changed."

Doctors discovered that Lyndsey was hemorrhaging in her brain, and she suffered a massive stroke as a result. The cause was a blood clot, which doctors believed developed from Lyndsey's use of NuvaRing, Diane said. They surgically removed two-thirds of her right cerebral hemisphere and transferred Lyndsey to a long-term acute care hospital, where, paralyzed, she was confined to her bed.

She remained there for six months and underwent additional surgeries, but nothing more could be done. In January 2009, doctors determined that Lyndsey had fewer than six months to live and recommended hospice care. She died one week after being admitted to hospice.

Lyndsey's death has been especially difficult for Dominic to comprehend, her mother said. Diane said her grandson continues to struggle with Lyndsey's absence, and it pains her that Lyndsey might still be alive had she been better informed about NuvaRing's side effects.

Diane Agresta is one of more than 1,500 plaintiffs[1] who are currently suing Merck over NuvaRing in mass litigation in federal court. They allege that the device was neither adequately tested nor appropriately labeled to warn women and their prescribing doctors about an increased risk of blood clots. The first trial in the consolidated multidistrict litigation is set for April in the Eastern District of Missouri.

Merck spokeswoman Kelley Dougherty disputed the claim that NuvaRing's manufacturers misled consumers about its side effects.

"The company has provided appropriate and timely information about NuvaRing to consumers and the medical, scientific and regulatory communities," Dougherty told HuffPost. "We remain confident in the safety and efficacy profile of NuvaRing -- which is supported by extensive scientific research -- and we will continue to always act in the best interest of patients."

During the pre-marketing negotiations over NuvaRing's packaging, the FDA ultimately acquiesced to Organon's demands. The label approved for NuvaRing in 2001 included a general warning about the risk of blood clots associated with most hormonal contraceptives. But it did not include a specific reference to the occurrence of a blood clot in a young, otherwise healthy woman in the clinical trial and its probable connection to NuvaRing.

Organon executives were pleased. "To my satisfaction a number of critical issues have been implemented in the current proposal of the FDA (e.g. the deletion of the single VTE case)," wrote Willem de Boer, the company's team leader for contraceptives in the regulatory affairs division, in a memo to his colleagues. Nancy Alexander, director of U.S. medical affairs, also wrote in an email that the "deletion of the single VTE case is good."

Alexander declined to comment, while messages to Muir were not returned. Attempts to locate Stern, de Boer and Mens were unsuccessful. Their intra-company email messages were revealed in a plaintiffs' expert witness report filed in the federal litigation.

"Blood clots have long been known as a risk associated with combined hormonal contraceptives," Dougherty told HuffPost. "The FDA-approved patient information and physician package labeling for NuvaRing include this information. All combination hormonal contraceptive products in the U.S., including NuvaRing, carry a boxed warning on serious cardiovascular events, especially in women who smoke."

Indeed, NuvaRing's website and advertisements state, "The risk of getting blood clots may be greater with the type of progestin in NuvaRing than with some other progestins in certain low-dose birth control pills." But, in the same breath, they state, "It is unknown if the risk of blood clots is different with NuvaRing use than with the use of certain birth control pills."

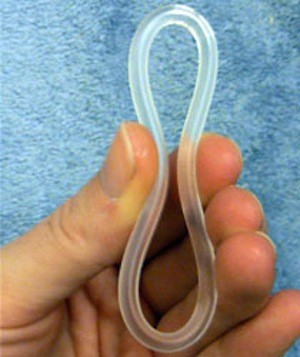

Like some other methods of birth control, NuvaRing releases the hormones estrogen and progestin. Once the ring is inserted in the vagina, the hormones are absorbed and distributed through the bloodstream over the course of three weeks. If used as directed, NuvaRing has a 99 percent efficacy rate in preventing pregnancy.

Whereas earlier versions of progestin raised the risk of blood clots slightly, NuvaRing contains a newer type of progestin called etonogestrel, a form of desogestrel. Researchers have found that these newer, so-called third- and fourth-generation progestins, including those containing desogestrel, carry a higher risk of blood clots.

Lawyers in the mass litigation have also suggested that NuvaRing’s unique delivery system may make blood clots more likely than with other hormonal contraceptives. Most birth control pills lose up to half their hormones in the digestive passage, whereas NuvaRing distributes hormones directly into the bloodstream. Due to its design, some NuvaRing users might experience spikes of estrogen that may expose them to a higher risk of blood clots.

One of Organon's own pre-marketing trials, known as Study No. 34218, found that estrogen levels shot up among two women at the start of the trial and two more women halfway through. Organon did not note this information in its 30-page summary report to the FDA, however, disclosing the bursts of estrogen only in the thousands of pages of material submitted to the agency as part of its new drug application for NuvaRing.

Kristine Kraft, a St. Louis attorney who is serving as co-lead counsel on behalf of the plaintiffs suing Merck in federal court, contends that Organon effectively covered up potential problems with NuvaRing's delivery of hormones.

"Was it provided to the FDA? Yes. But do you know how big a new drug application is? It's volumes and volumes," Kraft said. "So it's buried in that data, it's not in the summary. They did not footnote anything about the burst of estrogen being detected in these individual subjects of this study. It is, in our view, misleading."

Since NuvaRing's approval by the FDA in 2001, additional evidence of problems has surfaced. In clinical trials conducted between 2001 and 2004, three more cases of VTE were found among 20-something women. In all three cases, investigators concluded that the blood clots were "probably related" to NuvaRing.

An FDA-funded study released in 2011, which looked at more than 800,000 women using some form of birth control between 2001 and 2008, found that the risk of developing blood clots for NuvaRing users could increase by as much as 56 percent under some circumstances.

The following year, a study in Denmark[2] spanning several years and examining more than 1.6 million women caused even more alarm. It found that on average, women using a vaginal ring had an estimated 6.5-times increased risk of venous thromboembolism, compared to non-users of hormonal contraceptives of the same age.

One of the researchers in charge of the Danish study was Dr. Øjvind Lidegaard, whose previous findings on the increased VTE risk with birth control pills Yaz and Yasmin forced a label change for both products by their manufacturer, Bayer AG. The results of Lidegaard's NuvaRing study prompted a label change for NuvaRing, noting the increased risk of blood clots, in Canada.

In the United States, however, the FDA did not update NuvaRing's label to reflect Lidegaard's findings. Instead, it approved a label change in October 2013 that highlighted the results of one of Merck's own clinical trials[3] , as well as the 2011 FDA-funded study, on the last page of the NuvaRing package insert. Merck's study showed no increased risk among women using NuvaRing versus those taking combined oral contraceptives, whereas results included from the FDA-funded study showed only a slightly higher risk of VTE for NuvaRing users.

In 2001, the same year the FDA approved NuvaRing, the agency also approved another blockbuster contraceptive, Ortho McNeil's birth control patch Ortho Evra. Like NuvaRing, the patch is a combined hormonal contraceptive that releases hormones directly into the bloodstream, and it too was marketed as a more convenient alternative to taking a daily pill.

However, regulators found that the patch exposes women to higher levels of estrogen. On Nov. 10, 2005, the FDA approved a revised warning label[4] for Ortho Evra, which stated that users of the patch may be at a greater risk of developing blood clots.

Organon jumped at the opportunity to distinguish NuvaRing from its competitor. The company distributed a letter in November 2005 advising health care providers that NuvaRing delivered lower levels of estrogen than the patch. It also launched a training campaign among its sales representatives, instructing them to promote the differences between NuvaRing and Ortho Evra to health care professionals.

The labeling changes and negative media coverage surrounding Ortho Evra's safety caused the patch's sales to plummet[5] . U.S. prescriptions for the patch fell from 5 million in 2006 to approximately 1.3 million in 2011. Meanwhile, NuvaRing has gone on to become the most widely used non-pill contraceptive[6] in the world.

Sales representatives for Organon had already been instructed to discuss certain side effects of NuvaRing with physicians, such as headache, nausea, breast tenderness and bloating. They did not go into specifics about a potentially greater risk of blood clots. In a pretrial deposition, Sue Iannone, U.S. director of sales training at Organon, told lawyers representing the plaintiffs that doctors weren't typically interested in information about blood clots because the incidence of VTE was rare.

Yet Organon could not ignore forever the increasing number of women reporting having experienced blood clots while using NuvaRing. In August 2006, the company formed an "issue team" to address the growing crisis. That same month, Organon also met with Susan Allen, the former director of the FDA's Reproductive and Urologic Drug Products Division, to obtain an evaluation on the incidence of VTE reported to Organon and to help develop a communications strategy.

Allen had left the FDA earlier in 2006 and founded a consulting firm focused on regulatory issues. Organon contacted Allen again in 2007 to develop a strategy to respond to an FDA letter requesting that Organon conduct a U.S. safety study to assess NuvaRing's VTE risk.

At the FDA, Allen had overseen the regulation of reproductive and urologic drugs that were either marketed or proposed for marketing in the U.S., including NuvaRing. She was responsible for approving new drugs and ensuring that their labels were accurate. And it was her division that ultimately signed off on NuvaRing's approval.

Now she was working for the other side.

Allen is slated to appear as an expert witness on behalf of Merck in the trials over NuvaRing next year. The former FDA official did not return requests for comment. But Dougherty, Merck's spokeswoman, noted that Allen "has not worked for the FDA for several years." Dougherty said, "There is no conflict of interest with respect to her role in this litigation."

Allen's transition from government watchdog to drug company defender is, nonetheless, a prime example of the longstanding revolving door between the FDA and the pharmaceutical industry.

In December 2011, the FDA convened an independent advisory committee[7] to assess the safety of four popular third-generation combination oral contraceptives -- Yaz, Yasmin, Beyaz and Safyral -- amid concerns about excessive blood-clot risk. Despite several hours of emotional testimony from patients and family members who had lost a loved one, the panel voted 15-11 that the pills' benefits outweighed their risks. The Wall Street Journal later reported[8] that three of the doctors on the committee had financial ties to Bayer, the manufacturer of all four products.

A similar controversy had erupted in 2005, when it was revealed that 10 advisers on an FDA panel who voted in favor of keeping anti-inflammatories Celebrex, Bextra and Vioxx on the market had previously consulted[9] for the drugs' manufacturers. Had the advisers with ties to the Bextra and Vioxx manufacturers voted differently, neither drug would have remained on the market. Vioxx was later withdrawn after a study associated its use with approximately 60,000 deaths.

Following the uproar over Vioxx, the FDA developed new guidelines regarding potential conflicts of interest among its advisers. The guidelines called for the agency to issue a waiver that disclosed an adviser's links to a drug company -- and that would allow the adviser to vote -- only if no other specialists were available or if the individual's specific expertise were needed. But the agency failed to follow[10] its own new rules for its hearings on Yaz and Yasmin, choosing not to issue waivers or disclose some of its advisers' financial ties to Bayer. Ironically, it barred the panel's only consumer advocate, Sidney Wolfe, from voting, citing an "intellectual conflict of interest" based on criticism he had published regarding Yaz.

For Allen, this isn't her first time through the revolving door, either. Prior to joining the FDA in 1998, she headed Advances in Health Technology, a company set up by the Population Council -- the U.S. patent holder for abortion pill RU-486 -- to market the pill in the United States and train physicians on its use. At the FDA, she was in charge of the division that ultimately approved the drug; the agency declined to address whether Allen had recused herself from RU-486 issues.

In 2001, when the FDA approved NuvaRing without the stronger VTE warning label, the agency's power over how a drug was labeled and marketed was largely limited to the initial approval process. After a drug's approval, the FDA could recommend changes to the packaging and try to pressure the manufacturer, but it couldn't force the company to alter the label. Only in the case of serious and widespread safety issues could the agency take unilateral action and pull a drug from the market.

In 2007, Congress granted the FDA the authority to unilaterally impose a change to a drug's label, even after the drug had been approved. It also gave the agency the power to require drugmakers to conduct follow-up studies and clinical trials, rather than rely on their voluntary actions.

Even with this increased authority, however, public health advocates say the FDA has failed to wield its power aggressively enough. "The FDA, in my view, has not been as strong both prior approval and after approval in going with changes to strengthen the warnings or take the drug off the market," said Sidney Wolfe, speaking of the agency's work overall.

Wolfe and other advocates had hoped the FDA would include NuvaRing in its 2011 advisory committee hearing. Although the meeting primarily focused on Bayer's drospirenone-containing oral contraceptives (drospirenone is a fourth-generation progestin), the committee also voted 20-3 on another label change for Ortho Evra in light of ongoing concerns over its VTE risk. Several women who had used NuvaRing and other individuals who blamed it for the death of loved ones testified at the hearing, but the FDA declined to take action on the device.

"NuvaRing was never a topic for discussion" at the committee hearing, said FDA spokeswoman Andrea Fischer, explaining why the FDA declined to address concerns about the device at the time. "It was always intended to discuss the drospirenone-containing combined oral contraceptives and Ortho Evra. Some of the studies discussed at the meetings evaluated NuvaRing as one of many products studied, but this was not the focus of any discussion."

In light of the litigation over NuvaRing, a group of lawmakers is pressuring the FDA to flex its muscles. In September, Rep. Louise Slaughter (D-N.Y.) sent a letter, co-signed by five other House Democrats, to FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg requesting a label change warning women that NuvaRing presents an increased VTE risk.

"Such a label change would provide women and their doctors with critical information -- that a side effect of the drug is potentially life-threatening blood clots -- and better enable them to make informed healthcare decisions," the lawmakers wrote. "The current label does not provide adequate information to support women in making an informed decision, leaving a troubling information gap that affects many young, healthy women."

Groups supporting women's reproductive rights have also joined the chorus calling for a label that adequately reflects NuvaRing's VTE risk. Amy Allina, deputy director of the National Women's Health Network, said most hormonal contraceptives are "extraordinarily safe," so it's imperative that women are well informed about all the options available to them.

"This is a pretty critical issue," Allina told HuffPost. "There are some methods, including some pills on the market, that have a slightly higher risk than others. If the woman is informed about it, she can weigh the risk for herself, and that's why putting it in the label is so important."

"You need to trust us with the information," she added, emphasizing that the effort here was not to remove NuvaRing from the market but simply to explain the added risk to women and their health care providers.

"We think they're safe enough to have on the market as long as women know what they're getting into -- that for the benefit of this contraceptive, women are taking on a higher risk," Allina said. "It's small, but it's there. And this is not beyond a woman's ability to comprehend."

For Diane Agresta, that extra piece of information might have saved her daughter's life. "It just angers you as a mother for your child, for any other young woman or any other person, to not be informed," she said.

References

- ^ 1,500 plaintiffs (www.jdsupra.com)

- ^ study in Denmark (www.bmj.com)

- ^ Merck's own clinical trials (www.medpagetoday.com)

- ^ a revised warning label (www.fda.gov)

- ^ sales to plummet (www.bloomberg.com)

- ^ the most widely used non-pill contraceptive (www.nydailynews.com)

- ^ independent advisory committee (www.fda.gov)

- ^ later reported (online.wsj.com)

- ^ had previously consulted (www.sfgate.com)

- ^ failed to follow (www.washingtonmonthly.com)

- ^ Send us a tip (www.huffingtonpost.com)

- ^ Send us a photo or video (www.huffingtonpost.com)

- ^ Suggest a correction (www.huffingtonpost.com)

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Click to see the code!

To insert emoticon you must added at least one space before the code.